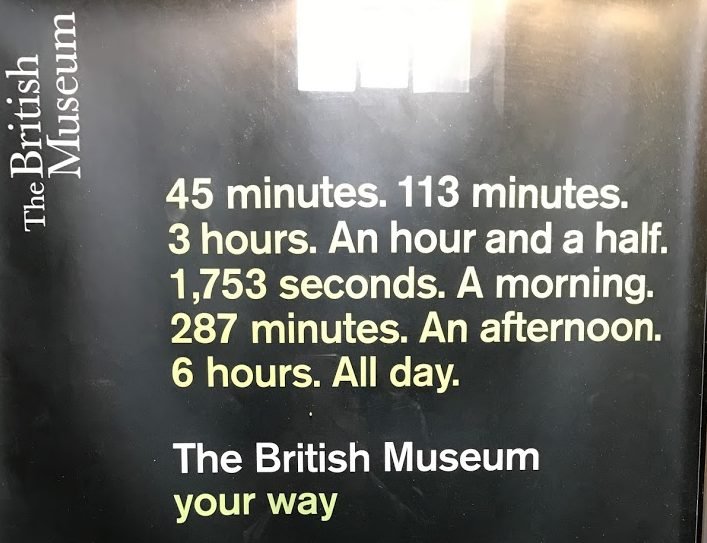

So far, London is spectacular. At least what I’ve seen of it, which is mostly the inside of the British Museum. Because let’s face it, we all know which person I am here:

It is entirely possible that I went straight there from the airport (having arrived at Heathrow shortly after eight in the morning), and stayed until I was literally shooed out at closing time. I also had to replace my audio guide when the battery died after several hours in the museum. So I guess I’ve confirmed my family’s suspicions on every vacation we take that I would just stay in that museum indefinitely if they didn’t drag me out.

But that museum! It exceeded my expectations. Which were high. I have been dying to spend a day in the British Museum ever since I read A History of the World in 100 Objects five years ago. The British Museum is a veritable temple for my little humanist heart, and I savoured every minute of it.

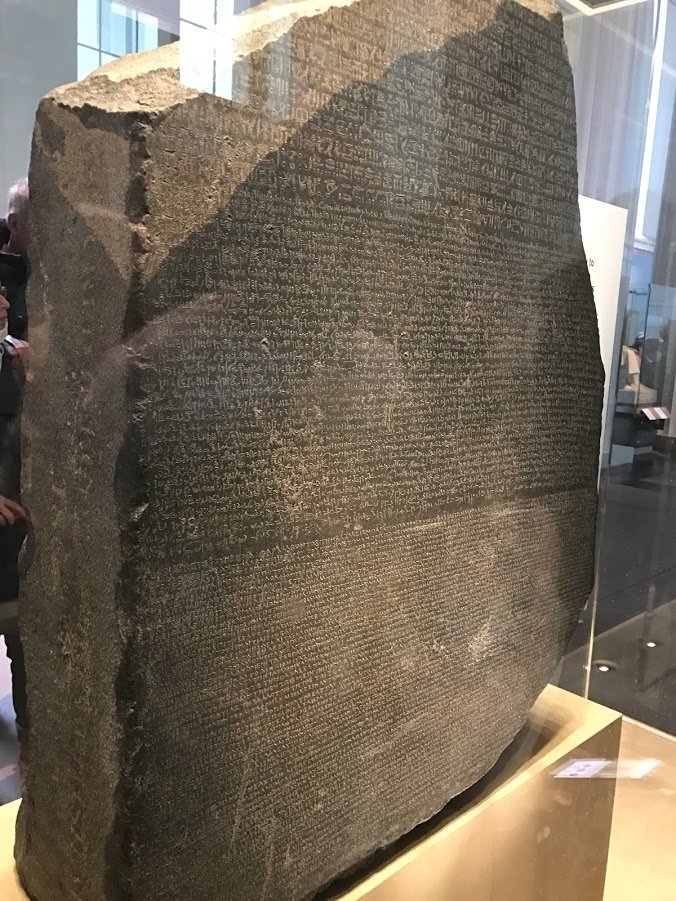

I think the first thing that would impress any visitor is the sheer breadth and quality of the collection. Not only does it house, for example, material from Ancient Egypt, Greece, Babylon, Assyria, and Rome, but its collection inculdes many of the most famous and iconic pieces emblematic of those civilisations.

This, for example, is the actual Rosetta Stone, which I saw with my own eyes.

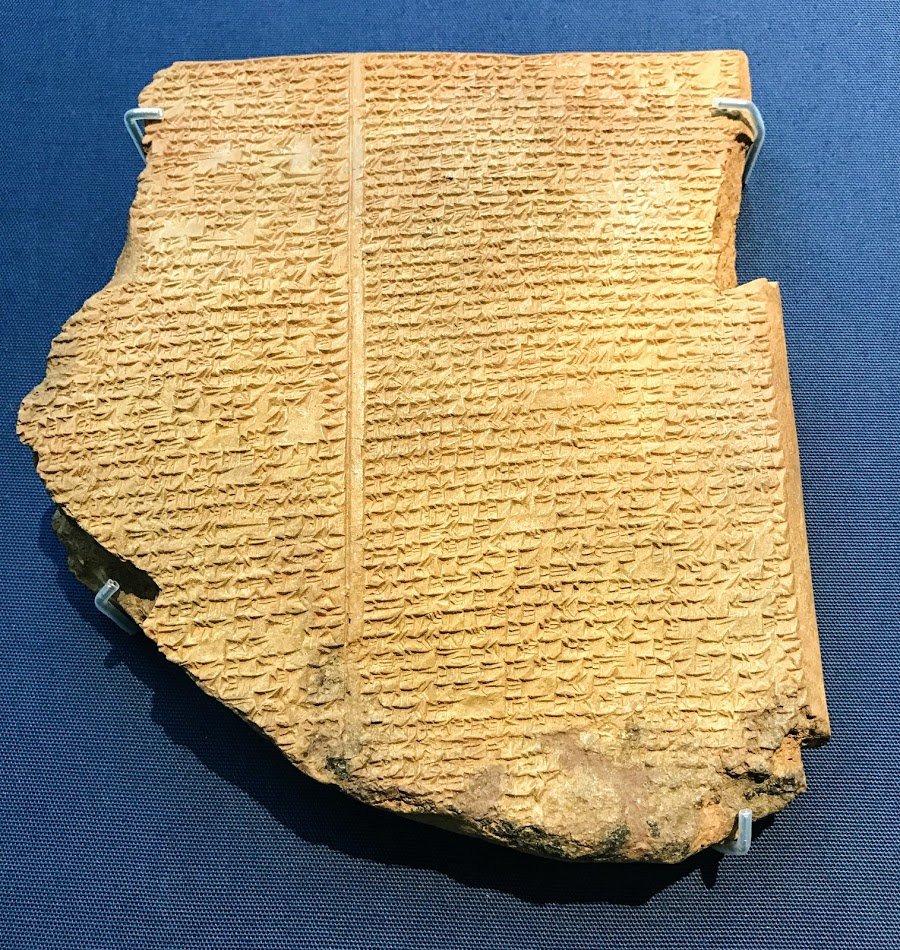

And THIS is the tablet with the flood story from the Epic of Gilgamesh from Ashurbanipal’s library.

Speaking of which library, the British Museum has it, all 30,000 clay tablets. One of the oldest libraries in the world, which was partially burned during the fall of Ninevah, paradoxically preserving the books because they were mostly written on clay tablets and got partially baked.

Luckier than the Library of Alexandria. I might have gotten a little sentimental and cried, because yes,

Which is why, as I told Tony the other day, I love working in an archive. Every day I go to work and feel like I’m preventing the lost Library of Alexandria from getting burned again.

Seeing that library made me think of something else, which was my second recurring feeling at the British Museum (after wonder and adoration over all the beautiful things we humans have created). Those 30,000 clay tablets are in something of disarray because they were not properly catalogued by the venerable British archaeologist who carted them off to Britain in the first place.

I get that these early European archalogists were amateurs by definition, since they were the ones who developed archaology as a discipline. And it’s also true that they probably saved some of these artifacts from destruction or loss. But a lot of them did considerable damage to the treasures they were supposedly preserving, and often they seemed more concerned with carrying off the best bits to Europe than keeping them intact or even describing and cataloging them properly.

One of the biggest cutural heritage debates in the world today is whether the treasures of history should remain where they are in European museums or go home to their countries of origin. I gather that the British Museum’s main argument is that these treasures belong to humanity as a whole, and anyone can come visit and view them for free. However, what that means in practice is mostly that British people and the privileged from other countries can go view them for free, since have you SEEN the prices of hotels in London? I’m fortunate to be bumming off Tony’s work and a kind friend who lives here. But let’s be honest; even though London is one of the most touristed cities in the world, the majority of the world’s population (including many people in the countries whose major historical treasures are held here) will never be able to afford to visit. I vividly remember going to museums and archaeological sites all over the Middle East and finding over and over again that the most dramatic and significant pieces were in exile at the Louve or the British Museum or some other European Institution.

Nowhere is this very public debate more visible than in the custom-created room where the sculptures from the Parthenon are kept. Since 1983 the Greek government has been trying to get these back. The visible evidence of this drama is obvious in the number of heads that are missing from statues because they are in Greece. One is left with the image of some kind of monumental struggle; it feels almost violent, if only because so many of the heads and bodies in question belong to the Lapiths and centaurs locked in battle in exquisitely carved metopes taken from the temple. It’s a sort of meta-history layered over the original one, a tale of cultural appropriation and warring national identities, the political forever inextricable from the artistic. I suppose that sort of tension is an oft-repeated theme in the museum’s long-running chronicle of human civilisation itself.

There was another related thing about the British Museum that really struck me: while it does indeed host objects relevant to the history of the whole human race, the presentation is entirely British. And 19th century British, at that. In a majority of cases, the explanatory text around the displays is a good deal more focused on whichever British colonial administrator/military commander cum amateur archaelogist is responsible for the arrival of the objects in question at the British Museum. The treasures of 6000 years of human history seem stuck in a sort of Victorian narrative: the sun never sets on the Empire, which is a direct inheritor and continuation of the glories of all former empires.

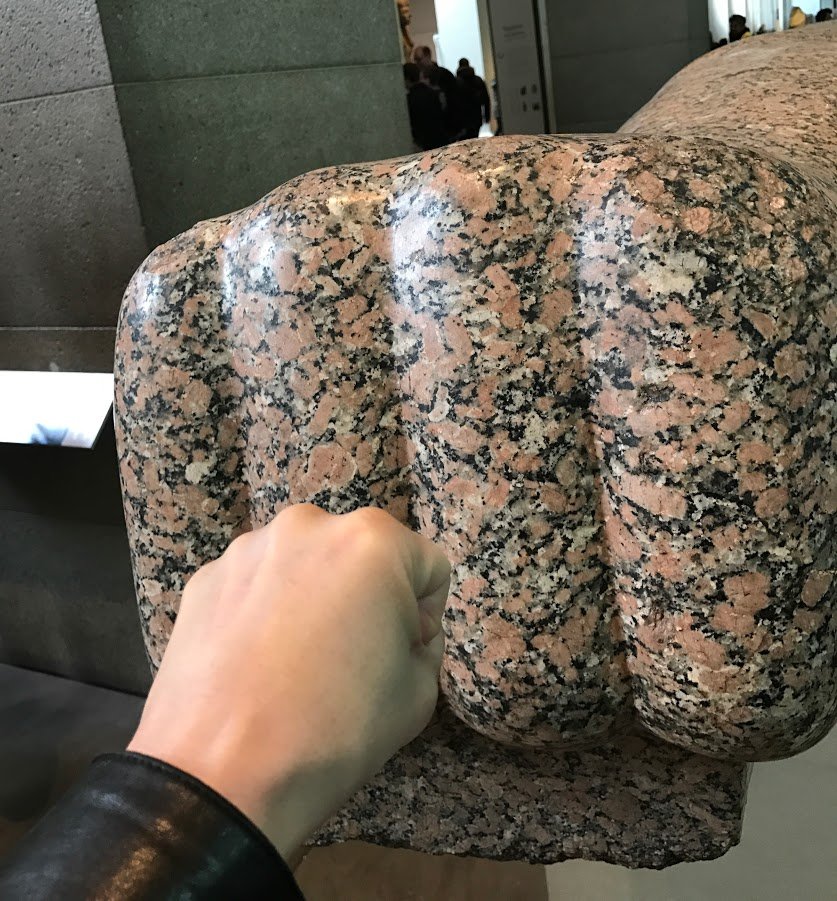

All that said, I adored the British Museum, and would have stayed longer had they been open later. And in fact, one of the things I perversely enjoyed was the very Britishness of it; the fact that as I was fist-bumping Ozymandias I could actually picture Shelley encountering the giant fragments of the statue of Ramses at the British Museum and being inspired to write the poem.

I’m fascinated by Britain in the long 19th century, at the peak of her power. I find the art and literature that came out of it beautiful and engaging. It’s far enough to feel like a bygone era, but close enough to feel tantalisingly relatable. And while I don’t exactly relate to this British idea of being inheritors of power, I like the thought that we are inheritors of culture; that Cyrus and Ashurbanipal and Aristotle and Marcus Aurelius and Muhammed are real people, and these are the things they touched and the words they wrote, and those things belong to all of us.

Pingback: Families in Global Transition Conference 2017 – Casteluzzo