My work trip in Berlin last month was mostly work, aside from a few nights out on the town with new friends. One evening we bonded at a Cuban cocktail bar over several pages of sugary cocktails, including some kind of hideously sweet bright green beer that is apparently a thing in Berlin.

Then there was an even more memorable evening where we randomly ended up in a German karaoke bar next to Alexanderplatz. Karaoke is one of those things that is so individually cultural, and yet simultaneously so weirdly universal. Suffice it to say that I heard the same Josh Groban song twice in one night.

My favourite evening was our last one together, during which I drank delicious hot chocolate at Rausch Shokoladenhaus in Mitte, had the best Syrian food I’ve eaten since, well, Syria, and as the night wore on, surreally found myself pretending to be Canadian to a very drunk and somewhat insistent German who had inexplicably pulled up a chair at our table. It turned out that this classic technique for avoiding wearisome conversations and hostility about American politics backfired on me a bit this time; he happened to be pining for Canada after having been deported from there last year, and knew far more about Canada than I did.

Eventually, half of our group went off to find somewhere to dance, but I was ready to call it a night. It was well after 2 a.m. when I finally ended up at my hostel, feeling inhumanly exhausted. Normally when one checks into one’s temporary lodgings in the middle of the night there is only one sleepy hotel employee, but here the party was still in full swing. There was loud dance music thumping in the bar downstairs, which was full of wide-awake backpackers. When I had originally booked my very first night alone in a hostel, it had seemed edgy and exciting to me. After all, I married young and did my crazy years of travel in my twenties with babies and toddlers in tow. Now I slunk through the revelers to find the back office and check in, suddenly feeling decidedly middle-aged and un-hip.

Morning came rather sooner than usual. After all this culture already, did I really need more? Yes, yes I did. I had been, of course, warned away from Museumsinsel by those in the know, because it is too obvious, too touristy, too traditional. It was my first time in Berlin, though, and I have a guilty passion for the plundered treasures and unbridled excesses of 19th century archaeology.

Ah, it was a short, heady, extraordinary time, this golden age of professional pillaging. Museology nerd that I am, I was fascinated at the Altes Museum (the one dedicated to antiquities) to find this timeline of the museum’s 350 year history. The timeline was about five times as long as the part I’ve captured here, but most of the good stuff ended up at the museum during the period of the bottom, purple bar: The Major Excavations, between the 1870’s and 1910.

Really, this period in European colonial archaeology lasted more like a hundred years, beginning with Napoleon’s 1798 invasion of Egypt, which soon resulted in the sensational acquisition of the Rosetta Stone and the awakening of Egyptomania in Europe. Shortly thereafter, Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, removed the so-called “Elgin Marbles” from the Parthenon, and the rest is (theft and appropriation of) history.

They had a real eye for the monumental, these archaeologists and their corresponding museum curators. The magnificent, priceless pieces of art and architecture they ripped up and carted home landed in places like the Louvre, the British Museum, and of course, Museumsinsel. In the European capitals these treasures had whole wings of museums built around them, designed to accentuate their colossalness as well as their beauty.

These displays give one the vertiginous feeling of traveling back to a time when power was absolute, and the little people like us were insignificant indeed compared to the divine royals invoked in every stone and brushstroke. I love the involuntary rush of the sublime that I feel when I step through these enormous portals, even as I simultaneously compose a meta-critique in my head. One cannot help wondering if the 19th century ruling elites (including many of these archaeologists) saw themselves as a reflection of that same power.

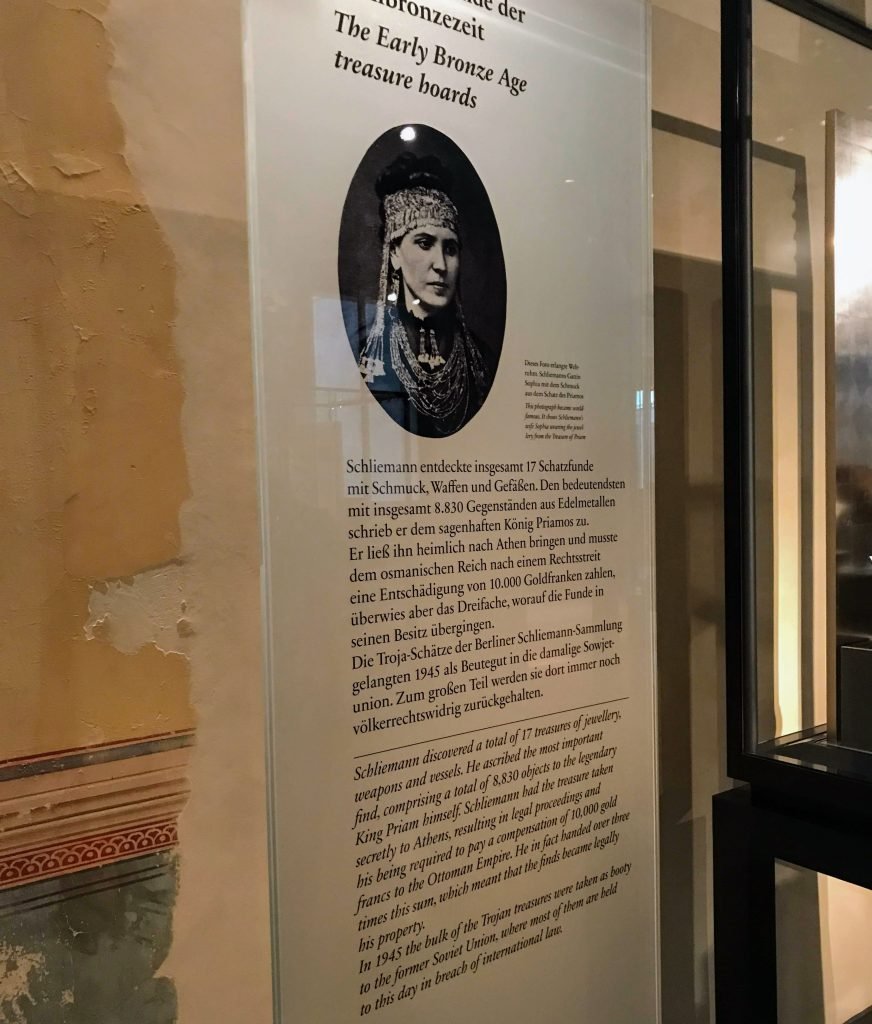

Nobody embodies this spirit of high-flung drama, pillaging, and egomania better than Heinrich Schliemann, German archaeologist, adventurer, and con-man extraordinaire. His story is long and colourful, but his most famous moment (immortalised in liberally fictionalised form by himself) came when he “singlehandedly discovered” the site of Ancient Troy. According to his embroidered diaries, he made this discovery by taking almost fanatically literally the geographical descriptions offered in the Iliad. Although many previous archaeologists had tried to locate the famous city, the prevailing opinion up to that time had been that Troy was a product of Homer’s imagination.

Schliemann’s varied career spanned everything from bookkeeper in Amsterdam (after he was a cabin boy on a ship bound for Venezuela, which wrecked off the Dutch coast) to Crimean War profiteer to–of course–archaeologist. Born in Germany, he spent a considerable time working in Russia, but also moved to the United States and lived there long enough to become an American citizen. There is no shortage of sensational material on Schliemann, and the sensationalisation is almost entirely of his own creation. One could almost choose at random; a brief but instructive insight into his character can be had from this excerpt out of his Wikipedia page:

Schliemann needed an assistant who was knowledgeable in matters pertaining to Greek culture. As he had divorced Ekaterina in 1869, he advertised for a wife in a newspaper in Athens. A friend, the Archbishop of Athens, suggested a relative of his, 17-year-old Sophia Engastromenos (1852–1932). Schliemann, age 47, married her in October 1869, despite the 30 year difference in age. They later had three children, Andromache, Troy, and Agamemnon Schliemann; he reluctantly allowed them to be baptized, but solemnized the ceremony in his own way by placing a copy of the Iliad on the children’s heads and reciting 100 hexameters.

Whatever can be said (and there is much) to cast aspersions on Schliemann’s character, business dealings, or archaeological methods, he was clearly a host unto himself. I have always been entranced by the iconic image (embroidered by himself) of him running excitedly along a hill near Hissarlik, Iliad in hand, “discovering” Troy. Compared to that, the fact that he subsequently blasted through nine layers of civilisation with dynamite (including the one from the actual time period of historical Troy) is mere postscript. Ahem.

I will say that it is not really fair to judge all of 19th century archaeology based on Schliemann, its most notorious amateur practitioner. Despite their wholesale ransacking of cultural heritage from sites across southern Europe, Africa, the Middle East and beyond, many of these archaeologists took their craft seriously, using the most up-to-date methods of the day and scrupulously cataloguing their findings.

Anyway, you can see why I was excited to see some of the thousands of artefacts Schliemann uncovered (and then creatively labelled to support his own ideas about classical antiquity). I particularly wanted to see a certain quintessential set of gold jewelry, which Schliemann famously photographed being worn by his above-mentioned young wife.

Sure enough, there they were:

Interestingly, there is surprisingly little of Schliemann’s Trojan treasure left in Berlin. In an ironic twist of fate, most of the pillaged treasure was re-pillaged by the Soviets after WWII and taken as booty to Moscow, where it largely remains. The Neues Museum, which houses what little Germany has retained of Schliemann’s treasure (as well as, most famously, Nefertiti, whose acquaintance I was also delighted to make), is obviously unhappy about the futility of their multiple efforts to get it back. But I can’t help but find the poetic justice of this meta-appropriation of appropriated cultural heritage rather satisfying. I think it’s quite a fitting footnote to the bizarre saga of Heinrich Schliemann, the Indiana Jones of 19th century archaeology.

Love this, and thanks especially for posting about the jewelry I’ve always remembered that story.

I was in the Egyptian Museum today, thinking about all the stuff that should have been there that’s elsewhere.

I spent a lot of time in the Egyptian Museum when I was in Cairo (many years ago). I think of it (and all those Middle Eastern archaeological sites) whenever I am in these European museums.

I feel like I have a running database in my head of statues missing heads, buildings missing façades, and vice versa. I’m always trying to mentally put things back together.